John Malkovich Talks About His All-Star Remix Album

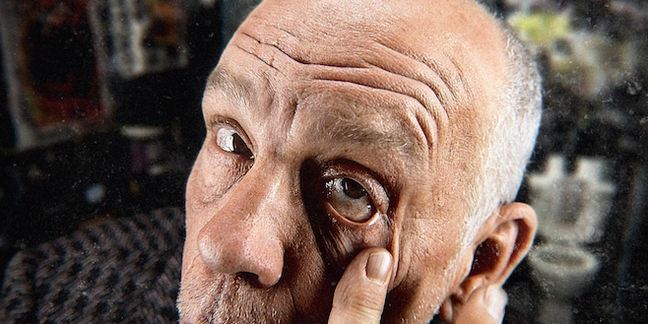

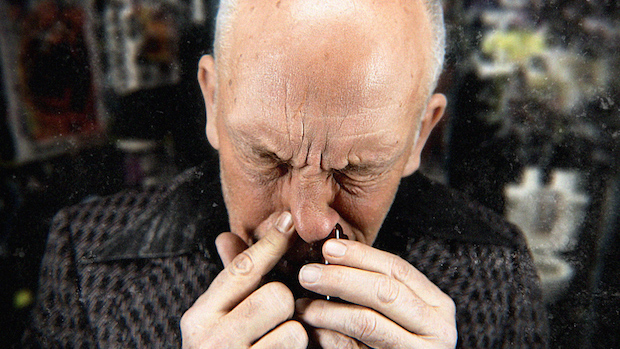

Photos by Sandro

Composer Eric Alexandrakis had an idea for an album: Get acting legend John Malkovich to read Plato’s Cave Allegory over some original ambient music, and then send the results to a bunch of musicians to remix and reinterpret Malkovich’s voice. The result is Like a Puppet Show, which is out on vinyl for Record Store Day‘s Black Friday event on November 27.

The album features contributions from Yoko Ono and Sean Lennon, OMD, Efterklang, Placebo, the Dandy Warhols, the Cars’ Ric Ocasek, Dweezil Zappa, Blondie’s Chris Stein, the Cranberries’ Dolores O’Riordan, and others. It’s accompanied by a series of photos of Malkovich by the photographer Sandro.

Pitchfork spoke to Malkovich and Alexandrakis on the phone about the album, the nature of collaboration, and what’s next for this project.

Pitchfork: John, how did you get involved with this album?

John Malkovich: Well, I think the idea came from Eric and Sandro, the photographer in Chicago that I’ve often collaborated with over the years on various things. [At the time of] the session, we did these reproductions or recreations of iconic photographs. There was also this idea to do a little short video, a film bit of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”, and then that went out to various musicians and composers and stuff.

Pitchfork: So the recording of your voice was done in conjunction with the video?

JM: Yeah.

Pitchfork: There are a lot of cooks in the kitchen here. John, when you heard the final product, were you at all surprised to hear how people distorted and mixed your voice?

JM: You never know what will happen with something that you put out in space—into the ether. So yeah, there’s always an element of surprise, I suppose, but, I mean, I think that’s quite a good thing. I was kept abreast of who might be doing the mix and who might not be and everything, but of course I had no idea what they would do with it. So yeah, there was some degree of surprise.

Pitchfork: Although these collaborations are sort of one-sided, does it still feel like an honor to be featured on songs with someone like Yoko Ono?

JM: I’ve gotten to collaborate a lot with musicians, but I think it’s always an honor, at least to me. As I said, whenever one does something and then it’s out there, you really have no idea whatsoever if it will affect someone in any way. If it does and they decide they want to use it as a base to build on or a base to tear apart [laughs], it doesn’t really matter much. I think that’s a great thing because I never have any expectation for anything I do. I have no expectation as to what degree of interest or lack thereof or inspiration or contempt it might arouse in people. I have no idea. So if people take it and decide to do something with it, I think it’s fantastic.

Pitchfork: Even though this is a handpicked list of contributors, the tone is sometimes wildly different from song to song. Some come out visceral or violent, and then something like Dweezil Zappa’s contribution seems much more lighthearted. Was cohesion ever a concern for this album or were you guys more open to the possibility of it being more chaotic?

EA: Not so much chaotic, but when you look at John’s portraits, everything has a different personality and a different vibe and a different character. The goal was really to keep it varied and not tell people what to do and let people experiment and express themselves in their own way, because that’s really the idea behind a lot of the imagery.

Pitchfork: What drew you to “The Allegory of the Cave”?

EA: Just thinking of John and looking at his work, he always seemed to me like a very philosophical, thinking, creative person, so something from a philosopher just seemed to make sense, and his voice just fits so well.

Pitchfork: John, you’ve just been compared to a philosopher. How do you feel about that, and what is your relationship with Plato’s allegory?

JM: Well, I think I probably hadn’t read it since philosophy class, and that was when I was very young and in school, but I like it. I think it’s a very interesting little allegory about truth and reality—about what is true meaning, is there true meaning, and if there is true meaning and one attempts to explain it or maybe even say it, what the cost of that may be. People believe all kinds of things, and sometimes if you go against those beliefs, you can run into a lot of trouble. I think that’s always a quite timely and succinct lesson.

As far as being a philosopher or being philosophical, I don’t see myself that way, but as Charlie Kaufman said in his script Being John Malkovich, in one sentence he was “the Schopenhauer of the 20th century” and in the next sentence he was an “overrated sack of shit.” I know at least one of those is true. But I don’t worry about things like that too much. I attempt to do the things that interest me, and I also attempt with collaborators that I trust to do the things that interest them. That’s how you learn something.

It wasn’t my idea to do this. It wasn’t my idea to work with Sandro, although we’ve worked together many times. Usually Sandro sets the agenda very much so for what we’re doing at a given session. Now, I’m very unlikely to reject or even quibble about the concept of the activities, but I’m very likely to try to accomplish them once that concept is set because as with these pieces that’s the point of artistic collaboration. It’s not always, “You do what I tell you.” It’s, “Here’s an idea—doesn’t so much matter who it was brought by. How do we work together to achieve a goal?” If you see what I mean. That’s—most especially in the work I’ve done, as Eric mentioned, a lot of classical music and musicians and with Sandro—how I would define what my role is in it.

Pitchfork: Eric mentioned earlier that there are further collaborations coming. What will those look like?

JM: Well, I imagine the three of us will do something else in the months or years to come. Sandro’s been pretty busy doing other stuff. As have I. We’re talking about a possible collaboration later this year on something which I don’t particularly want to talk about because it’s not all settled yet as far as I can tell—as much as I can gather. But yeah, I can see doing a lot of things. I think for the music, there are other people who have yet to put in their two cents. For instance, the French band AaRON, they’re going to do something. [They’re] young, French musicians that I worked with on something else earlier this year and I think there will be a number of other people and I look forward to hearing them. But that collaboration is…it’s really them. That’s them taking this idea and doing what they want with it. I wouldn’t dream of proffering a suggestion or even commenting because they’re all creative people.

Pitchfork: It’s been emphasized that this album isn’t coming out digitally. Why is it important that this exists solely as a physical object?

EA: The thinking is that art has value, and although digital revenue is high, keeping it physical at this point in time is really to show that it’s not disposable. Art is not disposable. If you want it, you have to hold it and smell it and touch it and read the credits and enjoy it and put it on your wall. I was at the shoot for the homage photos and watching all the work and the crew and the direction and the way John was portraying these characters and acting them out and all that. You can’t get that idea from just dragging an image off of a computer and onto your desktop and forgetting about it. Later down the line in a few years we’ll probably do a digital release anyway, but this creates the anticipation and demand for that.

Recent Comments